Whose Artwork Sparked a Debate on the Definiton of Art When It Was Taxed as a Plane Propeller

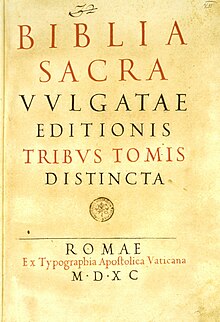

A copy of the Sixtine Vulgate, the Latin edition of the Catholic Bible printed in 1590 after many of the Council of Trent's reforms had begun to take identify in Cosmic worship

The Counter-Reformation (Latin: Contrareformatio), also called the Catholic Reformation (Latin: Reformatio Catholica) or the Catholic Revival,[1] was the menstruum of Cosmic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation, also known as the Protestant Revolution. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) and largely concluded with the determination of the European wars of religion in 1648.[ commendation needed ] Initiated to address the effects of the Protestant Reformation,[ citation needed ] the Counter-Reformation was a comprehensive effort equanimous of apologetic and polemical documents and ecclesiastical configuration as decreed by the Quango of Trent. The last of these included the efforts of Imperial Diets of the Holy Roman Empire, heresy trials and the Inquisition, anti-abuse efforts, spiritual movements, and the founding of new religious orders. Such policies had long-lasting effects in European history with exiles of Protestants continuing until the 1781 Patent of Toleration, although smaller expulsions took place in the 19th century.[two]

Such reforms included the foundation of seminaries for the proper training of priests in the spiritual life and the theological traditions of the Church building, the reform of religious life past returning orders to their spiritual foundations, and new spiritual movements focusing on the devotional life and a personal relationship with Christ, including the Spanish mystics and the French schoolhouse of spirituality.[1]

It also involved political activities that included the Spanish Inquisition and the Portuguese Inquisition in Goa and Bombay-Bassein etc. A primary emphasis of the Counter-Reformation was a mission to reach parts of the world that had been colonized every bit predominantly Catholic and besides endeavor to reconvert nations such equally Sweden and England that once were Catholic from the time of the Christianisation of Europe, but had been lost to the Reformation.[one]

Various Counter-Reformation theologians focused merely on defending doctrinal positions such equally the sacraments and pious practices that were attacked by the Protestant reformers,[1] upwards to the Second Vatican Quango in 1962–1965.[iii]

Key events of the period include: the Council of Trent (1545–63); the excommunication of Elizabeth I (1570), the codification of the uniform Roman Rite Mass (1570), and the Battle of Lepanto (1571), occurring during the pontificate of Pius V; the construction of the Gregorian observatory in Rome, the founding of the Gregorian Academy, the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, and the Jesuit China mission of Matteo Ricci, all under Pope Gregory Xiii (r. 1572–1585); the French Wars of Religion; the Long Turkish War and the execution of Giordano Bruno in 1600, under Pope Clement 8; the birth of the Lyncean Academy of the Papal States, of which the main figure was Galileo Galilei (later put on trial); the final phases of the Thirty Years' War (1618–48) during the pontificates of Urban Eight and Innocent X; and the germination of the last Holy League by Innocent Xi during the Smashing Turkish War (1683–1699).[ citation needed ]

Documents [edit]

Confutatio Augustana [edit]

Confutatio Augustana (left) and Confessio Augustana (right) being presented to Charles Five

The 1530 Confutatio Augustana was the Catholic response to the Augsburg Confession.

Council of Trent [edit]

Pope Paul III (1534–49) is considered the first pope of the Counter-Reformation,[ane] and he besides initiated the Quango of Trent (1545–63), tasked with institutional reform, addressing contentious issues such equally corrupt bishops and priests, the sale of indulgences, and other financial abuses.

The council upheld the bones structure of the medieval church building, its sacramental arrangement, religious orders, and doctrine. It recommended that the form of Mass should be standardised, and this took place in 1570, when Paul V made the Tridentine Mass obligatory.[4] It rejected all compromise with Protestants, restating basic tenets of the Catholic Organized religion. The council upheld salvation appropriated by grace through organized religion and works of that organized religion (not simply past faith, equally the Protestants insisted) because "organized religion without works is expressionless", as the Epistle of James states (2:22–26).

Transubstantiation, according to which the consecrated breadstuff and wine are held to have been transformed really and essentially into the body, claret, soul and divinity of Christ, was also reaffirmed, equally were the traditional seven sacraments of the Catholic Church. Other practices that drew the ire of Protestant reformers, such as pilgrimages, the veneration of saints and relics, the use of venerable images and statuary, and the veneration of the Virgin Mary were strongly reaffirmed as spiritually commendable practices.

The quango, in the Canon of Trent, officially accustomed the Vulgate listing of the Old Testament Bible, which included the deuterocanonical works (called apocrypha by Protestants) on a par with the 39 books found in the Masoretic Text. This reaffirmed the previous Quango of Rome and Synods of Carthage (both held in the 4th century Advertizing), which had affirmed the Deuterocanon as scripture.[a] The council too commissioned the Roman Canon, which served every bit administrative Church teaching until the Canon of the Catholic Church (1992).[ citation needed ]

While the traditional fundamentals of the Church were reaffirmed, there were noticeable changes to answer complaints that the Counter-Reformers were, tacitly, willing to admit were legitimate. Among the conditions to exist corrected past Catholic reformers was the growing split between the clerics and the laity; many members of the clergy in the rural parishes had been poorly educated. Frequently, these rural priests did non know Latin and lacked opportunities for proper theological training. Addressing the education of priests had been a fundamental focus of the humanist reformers in the by.[ commendation needed ]

Parish priests were to be improve educated in matters of theology and apologetics, while Papal authorities sought to educate the true-blue about the meaning, nature and value of fine art and liturgy, particularly in monastic churches (Protestants had criticised them every bit "distracting"). Notebooks and handbooks became more common, describing how to be expert priests and confessors.[ citation needed ]

Thus, the Council of Trent attempted to improve the discipline and assistants of the Church. The worldly excesses of the secular Renaissance Church, epitomized past the era of Alexander VI (1492–1503), intensified during the Reformation under Pope Leo X (1513–21), whose campaign to raise funds for the construction of Saint Peter'south Basilica by supporting use of indulgences served as a key impetus for Martin Luther's 95 Theses. The Catholic Church responded to these problems by a vigorous campaign of reform, inspired past earlier Catholic reform movements that predated the Quango of Constance (1414–17): humanism, devotionalism, legalism and the observantine tradition.[ citation needed ]

The quango, by virtue of its actions, repudiated the pluralism of the secular Renaissance that had previously plagued the Church: the organisation of religious institutions was tightened, discipline was improved, and the parish was emphasized. The appointment of bishops for political reasons was no longer tolerated. In the by, the big landholdings forced many bishops to be "absent bishops" who at times were property managers trained in administration. Thus, the Council of Trent combated "absenteeism", which was the practice of bishops living in Rome or on landed estates rather than in their dioceses. The Council of Trent gave bishops greater power to supervise all aspects of religious life. Zealous prelates, such as Milan'due south Archbishop Carlo Borromeo (1538–84), later canonized as a saint, fix an example past visiting the remotest parishes and instilling loftier standards.[ commendation needed ]

This 1711 analogy for the Index Librorum Prohibitorum depicts the Holy Ghost supplying the book burning burn.

Alphabetize Librorum Prohibitorum [edit]

The 1559–1967 Index Librorum Prohibitorum was a directory of prohibited books which was updated twenty times during the next four centuries as books were added or removed from the list by the Sacred Congregation of the Index. It was divided into iii classes. The start class listed heretical writers, the second class listed heretical works, and the 3rd grade listed forbidden writings which were published without the proper noun of the author. The Alphabetize was finally suspended on 29 March 1967.

Roman Catechism [edit]

The 1566 Roman Catechism was an attempt to brainwash the clergy.

Nova ordinantia ecclesiastica [edit]

The 1575 Nova ordinantia ecclesiastica was an addendum to the Liturgia Svecanæ Ecclesiæ catholicæ & orthodoxæ conformia, also called the "Scarlet Book".[5] This launched the Liturgical Struggle, which pitted John Iii of Sweden against his younger brother Charles. During this fourth dimension, Jesuit Laurentius Nicolai came to lead the Collegium regium Stockholmense. This theatre of the Counter-Reformation was chosen the Missio Suetica.[ citation needed ]

Defensio Tridentinæ fidei [edit]

The 1578 Defensio Tridentinæ fidei was the Catholic response to the Examination of the Council of Trent.

Unigenitus [edit]

The 1713 papal bull Unigenitus condemned 101 propositions of the French Jansenist theologian Pasquier Quesnel (1634–1719). Jansenism was a Protestant-leaning or mediating movement within Catholicism that was criticized for existence Crypto-Protestant. Later on Jansenism was condemned it led to the development of the Erstwhile Catholic Church building of kingdom of the netherlands.

Politics [edit]

British isles [edit]

Kingdom of the netherlands [edit]

Anabaptist Dirk Willems rescues his pursuer and is later on burned at the pale in 1569.

When the Calvinists took control of diverse parts of the netherlands in the Dutch Defection, the Catholics led by Philip II of Spain fought dorsum. The male monarch sent in Alexander Farnese equally Governor-General of the Spanish Netherlands from 1578 to 1592.

Farnese led a successful entrada 1578–1592 against the Dutch Defection, in which he captured the chief cities in the south Spanish – Belgium and returned them to the control of Catholic Kingdom of spain.[vi] He took reward of the divisions in the ranks of his opponents between the Dutch-speaking Flemish and the French-speaking Walloons, using persuasion to accept advantage of the divisions and foment the growing discord. Past doing so he was able to bring back the Walloon provinces to an fidelity to the king. By the treaty of Arras in 1579, he secured the support of the 'Malcontents', as the Catholic nobles of the south were styled.

The seven northern provinces also as the County of Flanders and Duchy of Brabant, controlled by Calvinists, responded with the Union of Utrecht, where they resolved to stick together to fight Spain. Farnese secured his base in Hainaut and Artois, then moved against Brabant and Flanders. City after city fell: Tournai, Maastricht, Breda, Bruges and Ghent opened their gates.

Farnese finally laid siege to the great seaport of Antwerp. The boondocks was open to the sea, strongly fortified, and well defended nether the leadership of Marnix van St. Aldegonde. Farnese cut off all admission to the sea by amalgam a bridge of boats across the Scheldt. Antwerp surrendered in 1585 as 60,000 citizens (60 per cent of the pre-siege population) fled north. All of the southern Netherlands was once again nether Castilian control.

In a war composed mostly of sieges rather than battles, he proved his mettle. His strategy was to offer generous terms for give up: at that place would be no massacres or annexation; historic urban privileges were retained; there was a full pardon and amnesty; return to the Catholic Church building would be gradual.[vii]

Meanwhile, Catholic refugees from the North regrouped in Cologne and Douai and adult a more than militant, Tridentine identity. They became the mobilizing forces of a popular Counter-Reformation in the South, thereby facilitating the eventual emergence of the country of Belgium.[8]

Germany [edit]

The Augsburg Acting was a menses where Counter-Reformation measures were exacted upon defeated Protestant populations following the Schmalkaldic War.

During the centuries of Counter Reformation, new towns, collectively termed Exulantenstadt, were founded especially as homes for refugees fleeing the Counter-Reformation. Supporters of the Unity of the Brethren settled in parts of Silesia and Poland. Protestants from the County of Flanders oftentimes fled to the Lower Rhine region and northern Germany. French Huguenots crossed the Rhineland to Central Frg. Most towns were named either after the ruler who established them or every bit expressions of gratitude, eastward.k. Freudenstadt ("Joy Town"), Glückstadt ("Happy Town").[9]

A list of Exulantenstädte:

- Altona, Hamburg

- Bad Karlshafen

- Freudenstadt

- Friedrichsdorf

- Glückstadt

- Hanau

- Johanngeorgenstadt

- Krefeld

- Neu-Isenburg

- Neusalza-Spremberg

Cologne [edit]

Peter Paul Rubens was the great Flemish artist of the Counter-Reformation. He painted Adoration of the Magi in 1624.

The Cologne War (1583–89) was a disharmonize between Protestant and Catholic factions that devastated the Electorate of Cologne. Afterwards Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, the archbishop ruling the expanse, converted to Protestantism, Catholics elected another archbishop, Ernst of Bavaria, and successfully defeated Gebhard and his allies.

Kingdom of belgium [edit]

Bohemia and Austria [edit]

In the Habsburg hereditary lands, which had become predominantly Protestant except for Tyrol, the Counter-Reformation began with Emperor Rudolf II, who began suppressing Protestant activity in 1576. This conflict escalated into the Bohemian Revolt of 1620. Defeated, the Protestant nobility and clergy of Bohemia and Republic of austria were expelled from the country or forced to convert to Catholicism. Amongst these exiles were important German poets such as Sigmund von Birken, Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg, and Johann Wilhelm von Stubenberg. This influenced the development of German Baroque literature, specially effectually Regensburg and Nuremberg. Some lived as crypto-Protestants.

Others moved to Saxony or the Margraviate of Brandenburg. The Salzburg Protestants were exiled in the 18th century, peculiarly to Prussia. The Transylvanian Landlers were deported to the eastern part of the Habsburg domain. As heir to the throne, Joseph II spoke vehemently to his mother, Maria Theresa, in 1777 against the expulsion of Protestants from Moravia, calling her choices "unjust, impious, incommunicable, harmful and ridiculous."[10] His 1781 Patent of Toleration tin can be regarded every bit the end of the political Counter-Reformation, although there were all the same smaller expulsions against Protestants (such as the Zillertal expulsion). In 1966, Archbishop Andreas Rohracher expressed regret about the expulsions.

France [edit]

Huguenots (French Reformed Protestants) fought a series of wars in French republic with Catholics, resulting in millions of deaths and the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 which revoked their liberty of religion. In 1565, several hundred Huguenot shipwreck survivors surrendered to the Castilian regime in Florida, presuming they would be treated fairly. The small number of Catholics among the shipwrecked were spared only the rest were all executed for heresy, with active clerical participation.[11]

Italian republic [edit]

Poland and Republic of lithuania [edit]

Spain [edit]

Eastern Rites [edit]

Middle East [edit]

Ukraine [edit]

The effects of the Quango of Trent and the counter-reformation also paved the way for Ruthenian Orthodox Christians to return to full communion with the Catholic Church building while preserving their Byzantine tradition. Pope Clement VIII received the Ruthenian bishops into full communion on February 7, 1596.[12] Nether the Treaty of the Matrimony of Brest, Rome recognized the Ruthenians' continued practice of Byzantine liturgical tradition, married clergy, and consecration of bishops from inside the Ruthenian Christian tradition. Moreover, the treaty specifically exempts Ruthenians from accepting the Filioque clause and Purgatory as a condition for reconciliation.[13]

Areas affected [edit]

The Counter-Reformation succeeded in drastically diminishing Protestantism in Poland, France, Italy, and the vast lands controlled by the Habsburgs including Austria, southern Germany, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), the Spanish Netherlands (now Belgium), Republic of croatia, and Slovenia. Noticeably, it failed to succeed completely in Republic of hungary, where a sizeable Protestant minority remains to this twenty-four hour period, although Catholics still are the largest Christian denomination.

Precursors [edit]

The 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries saw a spiritual revival in Europe, in which the question of conservancy became central. This became known as the Cosmic Reformation. Several theologians[ who? ] harkened back to the early days of Christianity and questioned their spirituality. Their debates expanded across most of the Western Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, whilst secular critics[ who? ] besides examined religious practice, clerical behavior and the church's doctrinal positions. Several varied currents of thought were active, but the ideas of reform and renewal were led by the clergy.[ citation needed ]

The reforms decreed at Fifth Council of the Lateran (1512–1517) had just a small effect.[ commendation needed ] Some doctrinal positions got further from the Church's official positions,[ citation needed ] leading to the break with Rome and the formation of Protestant denominations. Even then, conservative and reforming parties nonetheless survived within the Catholic Church building fifty-fifty as the Protestant Reformation spread. Protestants decisively broke from the Cosmic Church in the 1520s. The ii singled-out dogmatic positions within the Catholic Church solidified in the 1560s. The Catholic Reformation became known as the Counter-Reformation, defined equally a reaction to Protestantism rather than as a reform movement. The historian Henri Daniel-Rops wrote:

The term, however, though common, is misleading: it cannot rightly be applied, logically or chronologically, to that sudden awakening as of a startled giant, that wonderful endeavour of rejuvenation and reorganization, which in a infinite of thirty years gave to the Church an altogether new appearance. ... The so-called 'counter-reformation' did not begin with the Council of Trent, long after Luther; its origins and initial achievements were much anterior to the fame of Wittenberg. Information technology was undertaken, non past way of answering the 'reformers,' but in obedience to demands and principles that are role of the unalterable tradition of the Church and proceed from her most fundamental loyalties.[14]

The regular orders fabricated their first attempts at reform in the 14th century. The 'Benedictine Balderdash' of 1336 reformed the Benedictines and Cistercians. In 1523, the Camaldolese Hermits of Monte Corona were recognized as a split congregation of monks. In 1435, Francis of Paola founded the Poor Hermits of Saint Francis of Assisi, who became the Minim Friars. In 1526, Matteo de Bascio suggested reforming the Franciscan rule of life to its original purity, giving birth to the Capuchins, recognized by the pope in 1619.[15] This social club was well known to the laity and played an important role in public preaching. To respond to the new needs of evangelism, clergy formed into religious congregations, taking special vows only with no obligation to assist in a monastery's religious offices. These regular clergy taught, preached and took confession just were under a bishop's direct authority and not linked to a specific parish or area similar a vicar or canon.[fifteen]

In Italy, the first congregation of regular clergy was the Theatines founded in 1524 past Gaetano and Cardinal Gian Caraffa. This was followed past the Somaschi Fathers in 1528, the Barnabites in 1530, the Ursulines in 1535, the Jesuits, canonically recognised in 1540, the Clerics Regular of the Mother of God of Lucca in 1583, the Camillians in 1584, the Adorno Fathers in 1588, and finally the Piarists in 1621. In 1524,[ clarification needed ] a number of priests in Rome began to live in a community centred on Philip Neri. The Oratorians were given their constitutions in 1564 and recognized as an society by the pope in 1575. They used music and singing to attract the true-blue.[16]

Religious orders [edit]

New religious orders were a fundamental office of the reforms. Orders such equally the Capuchins, Discalced Carmelites, Discalced Augustinians, Augustinian Recollects, Cistercian Feuillants, Ursulines, Theatines, Barnabites, Congregation of the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri, and peculiarly Jesuits worked in rural parishes and set examples of Catholic renewal.

The Theatines undertook checking the spread of heresy and contributed to a regeneration of the clergy. The Capuchins, an offshoot of the Franciscan order notable for their preaching and for their care for the poor and the sick, grew rapidly. Capuchin-founded confraternities took special interest in the poor and lived austerely. Members of orders active in overseas missionary expansion expressed the view that the rural parishes oft needed Christianizing every bit much equally the heathens of Asia and the Americas.

The Ursulines focused on the special chore of educating girls,[17] the first gild of women to be dedicated to that goal.[xviii] Devotion to the traditional works of mercy exemplified the Catholic Reformation'south reaffirmation of the importance of both faith and works and salvation through God's grace and repudiation of the maxim sola scriptura emphasized by Protestants sects. Not only did they make the Church building more than effective, but they as well reaffirmed key premises of the medieval Church.[ citation needed ]

The Jesuits were the nearly effective of the new Cosmic orders. An heir to the devotional, observantine, and legalist traditions, the Jesuits organized along military lines. The worldliness of the Renaissance Church had no role in their new guild. Loyola's masterwork Spiritual Exercises showed the emphasis of handbooks feature of Catholic reformers before the Reformation, reminiscent of devotionalism.

Jesuits participated in the expansion of the Church in the Americas and Asia, by their missionary activity. Loyola's biography contributed to an emphasis on popular piety that had waned under political popes such as Alexander VI and Leo X. After recovering from a serious wound, he took a vow to "serve only God and the Roman pontiff, His vicar on Earth." The emphasis on the Pope is a reaffirmation of the medieval papalism, while the Council of Trent defeated conciliarism, the belief that general councils of the Church collectively were God'southward representative on Earth rather than the Pope. Taking the Pope as an absolute leader, the Jesuits contributed to the Counter-Reformation Church forth a line harmonized with Rome.

Devotion and mysticism [edit]

| The Boxing of Lepanto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Paolo Veronese |

| Twelvemonth | 1571 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 169 cm × 137 cm (67 in × 54 in) |

| Location | Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, Italy |

The Catholic Reformation was not only a political and Church policy oriented movement, just it also included major figures such as Ignatius of Loyola, Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, Francis de Sales, and Philip Neri, who added to the spirituality of the Catholic Church. Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross were Spanish mystics and reformers of the Carmelite Gild, whose ministry focused on interior conversion to Christ, the deepening of prayer, and delivery to God'due south will. Teresa was given the task of developing and writing about the way to perfection in her dearest and unity with Christ. Thomas Merton called John of the Cross the greatest of all mystical theologians.[19]

The spirituality of Filippo Neri, who lived in Rome at the same time equally Ignatius, was practically oriented, besides, but totally opposed to the Jesuit arroyo. Said Filippo, "If I have a real problem, I contemplate what Ignatius would do ... and then I do the exact opposite".[ citation needed ] As a recognition of their joint contribution to the spiritual renewal within the Catholic reformation, Ignatius of Loyola, Filippo Neri, and Teresa of Ávila were canonized on the same mean solar day, March 12, 1622.

The Virgin Mary played an increasingly central role in Cosmic devotions. The victory at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 was accredited to the Virgin Mary and signified the get-go of a strong resurgence of Marian devotions.[20] During and after the Catholic Reformation, Marian piety experienced unforeseen growth with over 500 pages of mariological writings during the 17th century alone.[21] The Jesuit Francisco Suárez was the first theologian to employ the Thomist method on Marian theology. Other well-known contributors to Marian spirituality are Lawrence of Brindisi, Robert Bellarmine, and Francis of Sales.

The sacrament of penance was transformed from a social to a personal experience; that is, from a public community deed to a private confession. It now took identify in private in a confessional. Information technology was a modify in its emphasis from reconciliation with the Church to reconciliation directly with God and from emphasis on social sins of hostility to private sins (chosen "the secret sins of the heart").[22]

Baroque art [edit]

The Cosmic Church was a leading arts patron beyond much of Europe. The goal of much fine art in the Counter-Reformation, peculiarly in the Rome of Bernini and the Flemish region of Peter Paul Rubens, was to restore Catholicism's predominance and centrality. This was ane of the drivers of the Baroque mode that emerged across Europe in the late sixteenth century. In areas where Catholicism predominated, architecture[23] and painting,[24] and to a lesser extent music, reflected Counter-Reformation goals.[25]

The Quango of Trent proclaimed that architecture, painting and sculpture had a role in conveying Catholic theology. Any work that might arouse "carnal desire" was inadmissible in churches, while whatever depiction of Christ's suffering and explicit agony was desirable and proper. In an era when some Protestant reformers were destroying images of saints and whitewashing walls, Catholic reformers reaffirmed the importance of art, with special encouragement given to images of the Virgin Mary.[26]

Decrees on art [edit]

| The Last Judgment | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Michelangelo |

| Year | 1537–1541 |

| Type | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 1370 cm × 1200 cm (539.three in × 472.4 in) |

| Location | Sistine Chapel, Vatican city |

The Last Judgment, a fresco in the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo (1534–1541), came under persistent attack in the Counter-Reformation for, among other things, nudity (later painted over for several centuries), non showing Christ seated or bearded, and including the pagan effigy of Charon. Italian painting after 1520, with the notable exception of the art of Venice, developed into Mannerism, a highly sophisticated style striving for effect, that concerned many Churchmen equally lacking entreatment for the mass of the population. Church building pressure to restrain religious imagery affected art from the 1530s and resulted in the decrees of the concluding session of the Council of Trent in 1563 including short and rather inexplicit passages concerning religious images, which were to have great bear upon on the development of Catholic art. Previous Catholic councils had rarely felt the demand to pronounce on these matters, unlike Orthodox ones which have ofttimes ruled on specific types of images.

The prescript confirmed the traditional doctrine that images only represented the person depicted, and that veneration to them was paid to the person, not the image, and further instructed that:

... every superstition shall be removed ... all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust ... in that location be nothing seen that is disorderly, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the business firm of God. And that these things may be the more faithfully observed, the holy Synod ordains, that no one be allowed to place, or crusade to exist placed, any unusual image, in any place, or church building, howsoever exempted, except that image have been canonical of by the bishop ...[27]

X years after the decree Paolo Veronese was summoned past the Holy Function to explain why his Terminal Supper, a huge canvas for the refectory of a monastery, independent, in the words of the Holy Office: "buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities" as well equally improvident costumes and settings, in what is indeed a fantasy version of a Venetian patrician feast.[28] Veronese was told that he must change his painting within a 3-calendar month flow. He just inverse the title to The Banquet in the Firm of Levi, even so an episode from the Gospels, but a less doctrinally central one, and no more was said.[29]

The number of such decorative treatments of religious subjects declined sharply, as did "unbecomingly or confusedly arranged" Mannerist pieces, as a number of books, notably by the Flemish theologian Molanus, Charles Borromeo and Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, and instructions past local bishops, amplified the decrees, often going into minute detail on what was acceptable. Much traditional iconography considered without adequate scriptural foundation was in effect prohibited, as was any inclusion of classical pagan elements in religious art, and almost all nudity, including that of the infant Jesus.[thirty]

According to the great medievalist Émile Mâle, this was "the death of medieval art",[31] but information technology paled in contrast to the Iconclasm nowadays in some Protestant circles and did not apply to secular paintings. Some Counter Reformation painters and sculptors include Titian, Tintoretto, Federico Barocci, Scipione Pulzone, El Greco, Peter Paul Rubens, Guido Reni, Anthony van Dyck, Bernini, Zurbarán, Rembrandt and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

Church building music [edit]

Reforms earlier the Council of Trent [edit]

The Quango of Trent is believed to be the noon of the Counter-Reformation's influence on Church music in the 16th century. However, the council's pronouncements on music were not the first try at reform. The Catholic Church had spoken out against a perceived abuse of music used in the Mass before the Council of Trent always convened to discuss music in 1562. The manipulation of the Creed and using non-liturgical songs was addressed in 1503, and secular singing and the intelligibility of the text in the delivery of psalmody in 1492.[32] The delegates at the council were just a link in the long chain of Church clergy who had pushed for a reform of the musical liturgy reaching back as far as 1322.[33]

Probably the nearly extreme move at reform came late in 1562 when, instructed by the legates, Egidio Foscarari (bishop of Modena) and Gabriele Paleotti (archbishop of Bologna) began piece of work on reforming religious orders and their practices involving the liturgy.[34] The reforms prescribed to the cloisters of nuns, which included omitting the employ of an organ,[ clarification needed ] prohibiting professional musicians, and banishing polyphonic singing, were much more strict than whatever of the council's edicts or even those to exist establish in the Palestrina legend.[35]

Fueling the cry for reform from many ecclesial figures was the compositional technique pop in the 15th and 16th centuries of using musical material and even the accompanying texts from other compositions such as motets, madrigals, and chansons. Several voices singing different texts in different languages made any of the text difficult to distinguish from the mixture of words and notes. The parody mass would then contain melodies (usually the tenor line) and words from songs that could have been, and oft were, on sensual subjects.[33] The musical liturgy of the Church was being more and more influenced by secular tunes and styles. The Quango of Paris, which met in 1528, as well as the Quango of Trent were making attempts to restore the sense of sacredness to the Church setting and what was advisable for the Mass. The councils were merely responding to issues of their twenty-four hour period.[36]

Reforms during the 22nd session [edit]

The Quango of Trent met sporadically from December 13, 1545, to December 4, 1563, to reform many parts of the Catholic Church. The 22nd session of the quango, which met in 1562, dealt with Church building music in Canon 8 in the department of "Abuses in the Sacrifice of the Mass" during a coming together of the council on September 10, 1562.[37]

Canon 8 states that "Since the sacred mysteries should be historic with utmost reverence, with both deepest feeling toward God alone, and with external worship that is truly suitable and condign, so that others may be filled with devotion and called to organized religion: ... Everything should be regulated so that the Masses, whether they be historic with the plain voice or in song, with everything clearly and quickly executed, may reach the ears of the hearers and quietly penetrate their hearts. In those Masses where measured music and organ are customary, null profane should exist intermingled, but only hymns and divine praises. If something from the divine service is sung with the organ while the service proceeds, permit if beginning be recited in a unproblematic, clear voice, lest the reading of the sacred words be imperceptible. Only the entire manner of singing in musical modes should exist calculated not to afford vain please to the ear, but then that the words may be comprehensible to all; and thus may the hearts of the listeners be defenseless up into the want for angelic harmonies and contemplation of the joys of the blest."[38]

Canon 8 is often quoted as the Council of Trent's decree on Church music, but that is a glaring misunderstanding of the canon; information technology was only a proposed decree. In fact, the delegates at the council never officially accepted canon 8 in its popular course just bishops of Granada, Coimbra, and Segovia pushed for the long argument about music to be adulterate and many other prelates of the council joined enthusiastically.[39] The only restrictions actually given by the 22nd session was to keep secular elements out of the music, making polyphony implicitly immune.[40] The issue of textual intelligibility did not make its way into the final edicts of the 22nd session but were only featured in preliminary debates.[41] The 22nd session just prohibited "lascivious" and "profane" things to be intermingled with the music but Paleotti, in his Acts, brings to equal importance the issues of intelligibility.[42]

The idea that the council chosen to remove all polyphony from the Church is widespread, but in that location is no documentary evidence to support that claim. It is possible, however, that some of the Fathers had proposed such a measure.[43] The emperor Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor has been attributed to be the "saviour of Church building music" because he said polyphony ought not to exist driven out of the Church. But Ferdinand was most likely an alarmist and read into the council the possibility of a total ban on polyphony.[44] The Council of Trent did not focus on the style of music only on attitudes of worship and reverence during the Mass.[45]

Saviour-Fable [edit]

The crises regarding polyphony and intelligibility of the text and the threat that polyphony was to exist removed completely, which was assumed to exist coming from the council, has a very dramatic fable of resolution. The fable goes that Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525/26–1594), a Church musician and choirmaster in Rome, wrote a Mass for the quango delegates in order to demonstrate that a polyphonic composition could set the text in such a style that the words could exist clearly understood and that was all the same pleasing to the ear. Palestrina's Missa Papae Marcelli (Mass for Pope Marcellus) was performed earlier the council and received such a welcoming reception amidst the delegates that they completely changed their minds and immune polyphony to stay in utilise in the musical liturgy. Therefore, Palestrina came to exist named the "saviour of Church polyphony". This legend, though unfounded, has long been a mainstay of histories of music.[46] The saviour-myth was first spread by an business relationship past Aggazzari and Banchieri in 1609 who said that Pope Marcellus was trying to replace all polyphony with plainsong.[47] Palestrina's "Missa Papae Marcelli" was, though, in 1564, afterwards the 22nd session, performed for the Pope while reforms were existence considered for the Sistine Choir.

The Pope Marcellus Mass, in short, was non important in its ain 24-hour interval and did not help salve Church polyphony.[48] What is undeniable is that despite whatever solid evidence of his influence during or after the Council of Trent, no figure is more than qualified to represent the cause of polyphony in the Mass than Palestrina.[49] Pope Pius IV upon hearing Palestrina's music would brand Palestrina, by Papal Brief, the model for time to come generations of Catholic composers of sacred music.[50]

Reforms following the Council of Trent [edit]

Like his contemporary Palestrina, the Flemish composer Jacobus de Kerle (1531/32–1591) was also credited with giving a model of limerick for the Council of Trent. His limerick in four-parts, Preces, marks the "official turning point of the Counter Reformation'south a cappella ideal."[51] Kerle was the only ranking composer of the Netherlands to take acted in conformity with the council.[52] Another musical behemothic on equal standing with Palestrina, Orlando di Lasso (1530/32–1594) was an important figure in music history though less of a purist than Palestrina.[53] He expressed sympathy for the council'due south concerns just still showed favor for the "Parady chanson Masses."[52]

Despite the dearth of edicts from the council regarding polyphony and textual clarity, the reforms that followed from the 22nd session filled in the gaps left by the council in stylistic areas. In the 24th session the council gave authorisation to "Provincial Synods" to discern provisions for Church music.[54] The decision to leave practical awarding and stylistic matters to local ecclesiastical leaders was important in shaping the future of Cosmic church music.[55] It was left then up to the local Church building leaders and Church musicians to find proper application for the quango's decrees.[56]

Though originally theological and directed towards the attitudes of the musicians, the Council's decrees came to be idea of by Church building musicians as a pronouncement on proper musical styles.[57] This agreement was most likely spread through musicians who sought to implement the quango's declarations just did not read the official Tridentine pronouncements. Church musicians were probably influenced by guild from their ecclesiastical patrons.[58] Composers who reference the council's reforms in prefaces to their compositions practise not fairly claim a musical ground from the council but a spiritual and religious ground of their fine art.[59]

The Cardinal Archbishop of Milan, Charles Borromeo, was a very important figure in reforming Church music after the Council of Trent. Though Borromeo was an adjutant to the pope in Rome and was unable to be in Milan, he eagerly pushed for the decrees of the council to be apace put into practice in Milan.[56] Borromeo kept in contact with his church in Milian through messages and eagerly encouraged the leaders at that place to implement the reforms coming from the Council of Trent. In ane of his messages to his vicar in the Milan diocese, Nicolo Ormaneto of Verona, Borromeo commissioned the master of the chapel, Vincenzo Ruffo (1508–1587), to write a Mass that would make the words as piece of cake to understand as possible. Borromeo as well suggested that if Don Nicola, a composer of a more chromatic manner, was in Milan he likewise could compose a Mass and the ii be compared for textural clarity.[lx] Borromeo was likely involved or heard of the questions regarding textual clarity because of his request to Ruffo.

Ruffo took Borromeo's committee seriously and set out to etch in a style that presented the text and then that all words would be intelligible and the textual meaning be the most of import part of the composition. His approach was to move all the voices in a homorhythmic fashion with no complicated rhythms, and to use dissonance very conservatively. Ruffo's approach was certainly a success for textual clarity and simplicity, merely if his music was very theoretically pure it was not an artistic success despite Ruffo's attempts to bring interest to the monotonous four-office texture.[61] Ruffo's compositional style which favored the text was well in line with the council's perceived business with intelligibility. Thus the belief in the council'southward stiff edicts regarding textual intelligibility became to characterize the development of sacred Church music.

The Quango of Trent brought near other changes in music: nigh notably developing the Missa brevis, Lauda and "Spiritual Madrigal" (Madrigali Spirituali). Additionally, the numerous sequences were mostly prohibited in the 1570 Missal of Pius Five. The remaining sequences were Victimae paschali laudes for Easter, Veni Sancte Spiritus for Pentecost, Lauda Sion Salvatorem for Corpus Christi, and Dies Irae for All Souls and for Masses for the Dead.

Another reform following the Quango of Trent was the publication of the 1568 Roman Breviary.

Calendrical studies [edit]

More than celebrations of holidays and similar events raised a need to have these events followed closely throughout the dioceses. But there was a trouble with the accuracy of the calendar: by the sixteenth century the Julian calendar was almost x days out of step with the seasons and the heavenly bodies. Among the astronomers who were asked to piece of work on the trouble of how the calendar could exist reformed was Nicolaus Copernicus, a canon at Frombork (Frauenburg). In the dedication to De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543), Copernicus mentioned the reform of the calendar proposed by the 5th Council of the Lateran (1512–1517). As he explains, a proper measurement of the length of the year was a necessary foundation to calendar reform. Past implication, his work replacing the Ptolemaic system with a heliocentric model was prompted in role past the demand for calendar reform.

An actual new agenda had to wait until the Gregorian calendar in 1582. At the time of its publication, De revolutionibus passed with relatively lilliputian annotate: little more than a mathematical convenience that simplified astronomical references for a more than authentic agenda.[62] Physical testify suggesting Copernicus's theory regarding the earth's motion was literally truthful promoted the apparent heresy against the religious idea of the time. Equally a result, during the Galileo affair, Galileo Galilei was placed nether house arrest, served in Rome, Siena, Arcetri, and Florence, for publishing writings said to be "vehemently suspected of existence heretical." His opponents condemned heliocentric theory and temporarily banned its didactics in 1633.[63] Similarly, the Academia Secretorum Naturae in Naples had been shut down in 1578. As a result of clerical opposition, heliocentricists emigrated from Catholic to Protestant areas, some forming the Melanchthon Circle.

Major figures [edit]

- Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582)

- Robert Bellarmine

- Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

- Charles Borromeo

- Peter Canisius (1521–1597)

- Erasmus

- John Fisher

- John of the Cross

- Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor (1578–1637)

- Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor (1640–1705)

- Louis Xiv (1638–1715)

- Ignatius of Loyola

- Mary I of England (1553–1558)

- Catherine de' Medici

- Thomas More

- Péter Pázmány (1570–1637)

- Philip II of Spain (1527–1598)

- Philip Neri (1515–1595)

- Pope Leo X (1513–1521)

- Pope Pius III (1503)

- Pope Paul Iii (1534–1549)

- Pope Julius III (1550–55)

- Pope Paul IV (1555–59)

- Pope Pius IV (1559–65)

- Pope Pius 5 (1566–72)

- Pope Gregory XIII (1572–85)

- Pope Sixtus 5 (1585–xc)

- Matteo Ricci (1552–1610)

- Central Richelieu (1585–1642)

- Francis de Sales

- Sigismund the Quondam of Poland (1467–1548)

- Sigismund III of Poland (1566–1632)

- Francis Xavier (1506–1552)

- Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

- William Five, Duke of Bavaria (1548–1626)

- Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria (1573-1651)

- Vincent de Paul

Meet also [edit]

- Anti-Papalism

- Anti-Protestantism

- Cosmic-Protestant relations

- Corpus Catholicorum (series)

- Counter-Reformation in Poland

- Crusades

- European wars of religion

- History of the Cosmic Church

- League for Catholic Counter-Reformation

- 2d scholasticism

- Spanish Inquisition

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e "Counter-Reformation". Encyclopædia Britannica Online . Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Der geschichtliche Ablauf der Auswanderung aus dem Zillertal [lit. 'The Historical Concatenation of Events of the Migration from the Ziller Valley'] (in German), 1837-auswanderer.de. Accessed 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Ceremony Thoughts". America. 7 October 2002. Archived from the original on nineteen Apr 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "General Teaching of the Roman Missal, no. 7". www.usccb.org. 2007. Retrieved 2019-06-07 .

- ^ Yelverton, Eric Esskildsen (1920). The Mass in Sweden: Its Development from the Latin Rite from 1531 to 1917. Issue 57 of Henry Bradshaw Society. Harrison and Sons. p. 75. ISSN 0144-0241. Swedish and English Translation of the Red Book.

- ^ de Groof, Bart (1993). "Alexander Farnese and the Origins of Mod Kingdom of belgium", Bulletin de 50'Institut Historique Belge de Rome, Vol. 63, pp 195–219.

- ^ Soen, Violet (2012). "Reconquista and Reconciliation in the Dutch Defection: The Campaign of Governor-General Alexander Farnese (1578–1592)", Journal of Early Modern History sixteen#ane pp 1–22.

- ^ Janssen, Geert H. (2012). "The Counter-Reformation of the Refugee: Exile and the Shaping of Catholic Militancy in the Dutch Revolt", Journal of Ecclesiastical History 63#4 pp. 671–692.

- ^ Martin, Christiane, ed. (2001). "Exulantenstadt". Lexikon der Geographie (in German). Heidelberg: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag. Retrieved 2020-05-30 .

- ^ Beales 2005, p. xiv. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBeales2005 (assist)

- ^ Henderson, Richard R.; International Council on Monuments and Sites. U.S. Commission; The states National Park Service (March 1989). A Preliminary inventory of Spanish colonial resource associated with National Park Service units and national historic landmarks, 1987. United States Commission, International Council on Monuments and Sites, for the U.Due south. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service. p. 87. ISBN9780911697032.

- ^ Union of Brest. Catholic Encyclopedia (1917), via newadvent.org.

- ^ Meet text of the Treaty of the Wedlock of Brest

- ^ Daniel-Rops, Henri. "The Catholic Reformation". EWTN – via the fall 1993 event of The Dawson Newsletter.

- ^ a b Péronnet, Michel (1981). Le XVe siècle (in French), Hachette U, p. 213.

- ^ Péronnet (1981). p. 214.

- ^ "The Ursulines". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

A religious order founded past St. Angela de Merici for the sole purpose of educating young girls

- ^ Hughes, Philip (1960) [1957]. A Popular History of the Reformation, Garden City, New York: Image Books, Ch. 3, "Revival and Reformation, 1495–1530", Sec. iii, "The Italian Saints", p. 86.

- ^ "Rise of Mount Carmel". John of the Cross. Image Books. 1958.

- ^ Stegmüller, Otto (1967). "Barock" (in German). Lexikon der Marienkunde. Regensburg, p. 566.

- ^ A Roskovany, conceptu immacolata ex monumentis omnium seculorum demonstrate 3, Budapest 1873

- ^ {{Cite journal |writer=[[John Bossy|Bossy, John |title= The Social History of Confession in the Age of the Reformation |journal= Transactions of the Royal Historical Society |volume= 25 |pages= 21–38 |twelvemonth= 1975 |jstor = 3679084 |doi= x.2307/3679084}}

- ^ Kruft, Hanno-Walter (1994). The Counter-Reformation, Baroque and Neo-classicism. A History of Architectural Theory. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 93–107. ISBN9781568980102.

- ^ Gardner, Helen; Kleiner, Fred S. (2010). Gardner'southward Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Cengage Learning. p. 192. ISBN9780495573647.

- ^ Hauser, Arnold (1999). Social History of Art, Volume 2: Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque. Psychology Press. p. 192. ISBN9780203981320.

- ^ Earls, Irene (1996). Baroque Art: A Topical Lexicon. pp. 76–77.

- ^ Text of the 25th decree of the Council of Trent

- ^ "Transcript of Veronese'due south testimony". Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2008-07-08 .

- ^ Rostand, David (1997). Painting in Sixteenth-Century Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, 2nd ed., Cambridge Up ISBN 0-521-56568-v

- ^ Blunt, Anthony, (1940; refs to 1985 edn). Creative Theory in Italia, 1450–1660, chapter VIII, particularly pp. 107–128, OUP, ISBN 0-19-881050-4

- ^ The death of Medieval Fine art. Extract from book past Émile Mâle

- ^ Fellerer, G. G. and Hadas, Moses. "Church building Music and the Council of Trent". The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. iv (1953) in JSTOR. p. 576.

- ^ a b Manzetti (1928). p. 330.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. 20.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. 21.

- ^ Fellerer and Hadas. pp. 580–581.

- ^ Fellerer and Hadas. p. 576.

- ^ Monson (2002). p.ix.

- ^ Monson (2002). pp. 10–11.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. 12.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. 22.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. 24.

- ^ Manzetti (1928). p. 331.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. sixteen.

- ^ Fellerer and Hadas. p. 576.

- ^ Davey, Henry. "Giovanni Pierluigi, da Palestrina", Proceedings of the Musical Association, 25th Sess. (1898–1899), p. 53. in JSTOR.

- ^ Davey. p. 52.

- ^ Smith, Carleton Sprague and Dinneen, William (1944). "Recent Piece of work on Music in the Renaissance", Modern Philology, Vol. 42, No. 1, p. 45. in JSTOR.

- ^ Manzetti (1928). p. 332.

- ^ Davey. p. 52.

- ^ Smith and Dinneen (1944). p. 45.

- ^ a b Leichtentritt (1944). p. 326.

- ^ Davey. p. 56.

- ^ Fellerer and Hadas. 576–577.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. 27.

- ^ a b Lockwood (1957). p. 346.

- ^ Fellerer and Hadas. 592–593.

- ^ Monson (2002). p. 26.

- ^ Fellerer and Hadas. 576–594.

- ^ Lockwood (1957). p. 348.

- ^ Lockwood (1957). p. 362.

- ^ Burke, James (1985). The Day the Universe Inverse. London Writers Ltd. p. 136.

- ^ Burke 1985, p. 149.

Notes [edit]

- ^ Eastern Orthodox churches, following the Septuagint, generally include the deuterocanonical works with even a few additional items non establish in Cosmic Bibles, but they consider them of secondary say-so and non on the same level every bit the other scriptures. The Church of England may utilize Bibles that place the deuterocanonical works betwixt the protocanonical Old Testament and the New, only not interspersed among the other One-time Testament books as in Cosmic Bibles.

Bibliography [edit]

- Leichtentritt, Hugo (1944). "The Reform of Trent and Its Effect on Music". The Musical Quarterly, Vol. xxx, No. 3. in JSTOR.

- Lockwood, Lewis H. (1957). "Vincenzo Ruffo and Musical Reform after the Council of Trent". The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 43, No. iii, in JSTOR.

- Manzetti, Leo P. (1928). "Palestrina". The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 3, in JSTOR.

- Monson, Craig A. (2002). "The Quango of Trent Revisited." Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 55, No. 1, in JSTOR

Further reading [edit]

General works [edit]

- Bauer, Stefan. The Invention of Papal History: Onofrio Panvinio between Renaissance and Catholic Reform (2020).

- Bireley, Robert. The Refashioning of Catholicism, 1450–1700: A Reassessment of the Counter Reformation (1999) excerpt and text search

- Dickens, A. G. The Counter Reformation (1979) expresses the older view that information technology was a movement of reactionary conservatism.

- Harline, Craig. "Official Faith: Popular Religion in Contempo Historiography of the Catholic Reformation", Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte (1990), Vol. 81, pp 239–262.

- Jones, Martin D. West. The Counter Reformation: Religion and Society in Early Modern Europe (1995), accent on historiography

- Jones, Pamela Yard. and Thomas Worcester, eds. From Rome to Eternity: Catholicism and the Arts in Italy, ca. 1550–1650 (Brill 2002) online

- Lehner, Ulrich L. The Catholic Enlightenment (2016)

- Mourret, Fernand. History of the Catholic Church (vol five 1931) online free; pp. 517–649; by French Catholic scholar

- Mullett, Michael A. The Cosmic Reformation (Routledge 1999) online

- O'Connell, Marvin. Counter-reformation, 1550–1610 (1974)

- Ó hAnnracháin, Tadhg. Catholic Europe, 1592–1648: Centre and Peripheries (2015). doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199272723.001.0001.

- Ogg, David. Europe in the Seventeenth Century (6th ed., 1965). pp 82–117.

- Olin, John C. The Cosmic Reformation: Savonarola to Ignatius Loyola: Reform in the Church building, 1495–1540 (Fordham University Press, 1992) online

- O'Malley, John Westward. Trent and All That: Renaming Catholicism in the Early on Modernistic Era (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

- Pollen, John Hungerford. The Counter-Reformation (2011) excerpt and text search

- Soergel, Philip G. Wondrous in His Saints: Counter Reformation Propaganda in Bavaria. Berkeley CA: University of California Printing, 1993.

- Unger, Rudolph K. Counter-Reformation (2006).

- Wright, A. D. The Counter-reformation: Catholic Europe and the Non-christian World (2nd ed. 2005), advanced.

Primary sources [edit]

- Luebke, David, ed. The Counter-Reformation: The Essential Readings (1999) excerpt and text search

Historiography [edit]

- Bradshaw, Brendan. "The Reformation and the Counter-Reformation", History Today (1983) 33#eleven pp. 42–45.

- Marnef, Guido. "Belgian and Dutch Mail service-war Historiography on the Protestant and Catholic Reformation in kingdom of the netherlands", Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte (2009) Vol. 100, pp. 271–292.

- Menchi, Silvana Seidel. "The Age of Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Italian Historiography, 1939–2009", Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte (2009) Vol. 100, pp. 193–217.

External links [edit]

- The Cosmic Counter-Reformation in the 21st Century

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counter-Reformation